Si può trasferire in gesto e movimento la scrittura così densa di racconto e di significato de La Tempesta di Shakespeare?

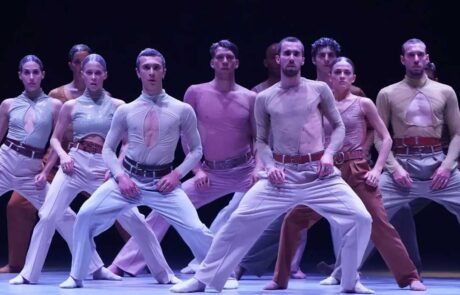

Questa la sfida dello spettacolo firmato da Giuseppe Spota: mettere alla prova la capacità della danza di raccontare una narrazione teatrale, illuminandone le storie e i personaggi in modo originale, osservandoli da nuovi punti di vista, garantendo una chiara leggibilità della vicenda originale senza rinunciare ad aprire spazi immaginativi inconsueti.

Sulle musiche originali di Giuliano Sangiorgi, Tempesta è la strada per una diffusione più capillare della danza e per rivolgerci a nuovi spettatori: segna il nostro avvicinamento al mondo del teatro.

Choreography Giuseppe Spota

Original music Giuliano Sangiorgi

Dramaturgy Pasquale Plastino

Set design Giacomo Andrico

Critical consultant Antonio Audino

Costume design Francesca Messori

Lighting design Carlo Cerri

Duration 70’ – For 16 dancers

Production Fondazione Nazionale della Danza / Aterballetto

In coproduction with CTB – Centro Teatrale Bresciano, Teatro Stabile del Veneto

Supported by Fondazione I Teatri Reggio Emilia

In partnership with Piccolo Teatro di Milano – Teatro d’Europa

Technical sponsor Pro Music

WORLD PREMIERES

June 12th,13th, 14th 2018, Milan, Piccolo Teatro Strehler

Set construction Fondazione I Teatri Reggio Emilia scene department

Costume construction Fondazione Nazionale della Danza / Aterballetto costume department – Francesca Messori, Debora Baudoni and Filippo Guggia

Thanks to

Rossella Zucchi, Set maker

Giorgia Amabili, Set designer assistant

Tommaso and Federico Fornari for the precious partecipation in the opening video

Can the wealth of writing and meaning in this work be transferred into gesture and movement?

This is the challenge facing the performance. It is an extremely arduous one because it invites a comparison with a text that has a special and absolute value in the whole of Shakespeare’s output. It is his last work and is considered as his spiritual testament, an adieu to the theatre and it is no coincidence that it presents a creator of magic onstage which, as Strehler rightly understood, alludes to a creator of theatrical wonders. In this case the playwright renews his theatrical language, offers an unusual emotional and narrative development, abandons continual changes of place and character, densely interwoven actions and leaps in time. Here there is just one place, one story and one time, according to the rules of Aristotle, which the author observes for the first time, voluntarily paying a final tribute to the idea of theatre in its purest form.

The choreographic creation meets this purity and creative linearity, but Shakespeare continues to evoke endless suggestions and dance can also grant itself the freedom to abandon the text to tell a story in another way, to evoke differently, to open up unusual imaginative realms, while continuing to follow the outline of the original narration.

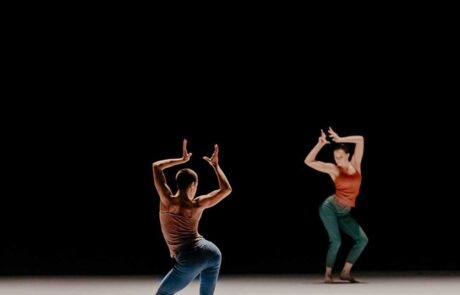

At the centre, there is still the story of a father and daughter. Prospero, the Duke ousted by his brother Antonio, and Miranda who has lived on the island from such a young age that she has no memory of any other place but this. From this conflict between the two men come images like those from a far-off past in black and white, and then there is the long tale that the father tells his daughter, of his noble birth and his arrival in that lost corner of the world, which is transformed into a visual calligraphy, until the tempest that brings Antonio, his ally the King of Naples and his son Ferdinand to the island. The tempest is caused by Prospero, as if it were a great game created for Miranda’s birthday, with the aim of changing the course of things for everyone. In this transcription in gesture and movement, the only being who lives on the island, Caliban, multiplies, to become a complex, multiple entity, who appears to be born from the waves of the sea, whence he will return. Ariel never touches the ground. He is continually pushed away by the element that bears his name.

However, there is a central passage in the work that this choreographic transposition focuses on: Prospero’s initial project is one of revenge. He wants to regain his power and authority over his brother and his allies. Just a few words from Ariel, a non-human creature moved by the suffering of those ship-wrecked, make him change his mind and put him suddenly on the road to pardon, eliminating his resentment, leading him to arrange a marriage between his daughter and Ferdinand and to overcome all of his conflicting instincts. This passage is often overlooked, but it is the central theme of the whole of Shakespeare’s work. It is as if the poet wanted to repudiate his revenge tragedies and the succession of losses to launch a new, more profound message of greater humanity. Thus, the story is resolved in the sign of mercy, of understanding between individuals, outlining a bright future through the young people and leading all those who have temporarily inhabited this place to abandon it. The island and Caliban go back to being fluctuating magma.

Antonio Audino – critical consultant

When I studied the text, one image led to another (as happens with Shakespeare’s work, in a continual domino effect) allowing the imagination to expand.

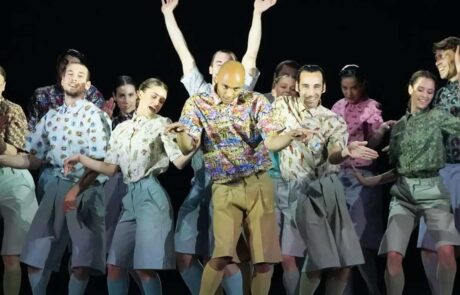

One of the things I was most fascinated by was the island, where a father (Prospero) and a daughter (Miranda) spend twelve years together with non-human beings and far from any forms of civilisation. Just like in a journey, at every stage the body and movement change and develop, drawing the public into a magical world at the centre of which is Caliban, Prospero’s servant, linked to Miranda by a relationship that transforms over the years.

Giuseppe Spota – choreographer

Dealing with Tempesta meant looking for a key to tell a story without using words. That’s why I created a musical installation, in which bodies themselves become the dialogue.

Giuseppe Spota and I understood each other wonderfully: I composed while he and Pasquale Plastino created the dramaturgy. When we compared our work, I discovered there was a natural harmony, which allowed me to find the mood for my composition.

I moved a lot as I wrote, and I think that’s how I saw the individual characters. For example, Caliban has a tribal aspect, which is displayed to us through the sound of wood, and I imagined a monster who contains a multitude of persons, in a modern key, of course.

I think there’s a happiness that the characters never achieve: I perceive the central theme of Tempesta to be a kind of melancholy.

Giuliano Sangiorgi – original music

The greatness of true classics is definitely based on how indestructible their value is when they are pulled in all possible directions by countless interpretations.

Shakespeare’s work is a prime example. The direction and dramaturgy have been read and interpreted in thousands of ways, not all of them by any means successful.

However, the text remains imposing, solid, authoritative, resistant to cracks and repeated violence, irradiating and capturing everyone with its poetic nature, continuing to provoke deep emotions.

How can dance compare with a written text where the words are vital to provoke these contrasting feelings?

We chose to give a ‘body’ to everything that is said in the text but never seen.

Pasquale Plastino – dramaturgy